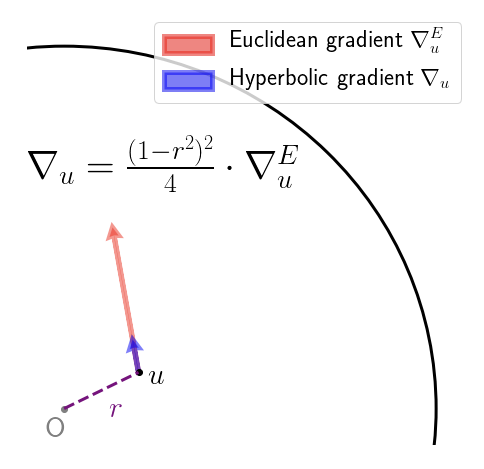

Nickel & Kiela had a great paper on embedding graphs in hyperbolic space at NIPS 2017. They work with the Poincaré ball model of hyperbolic space. This is just the interior of the unit ball, equipped with an appropriate Riemannian metric. This metric is conformal, meaning that the inner product on the tangent spaces on the Poincare ball differ from that of the (Euclidean) ambient space by only a scalar factor. This means that the hyperbolic gradient $\nabla_u$ at a point $u$ can be obtained from the Euclidean gradient $\nabla^E_u$ at that same point just by rescaling. That is, you pretend for a moment that your objective function is defined in Euclidean space, calculate the gradient as usual, and just rescale. This scaling factor depends on the Euclidean distance $r$ of $u$ from the origin, as depicted below:

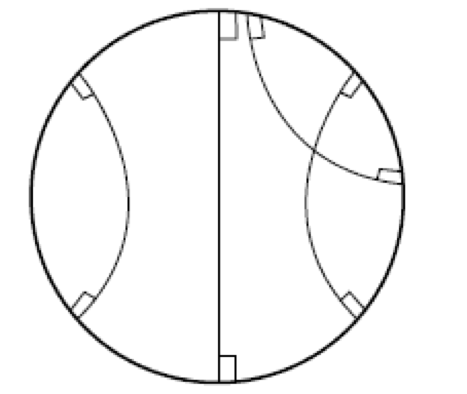

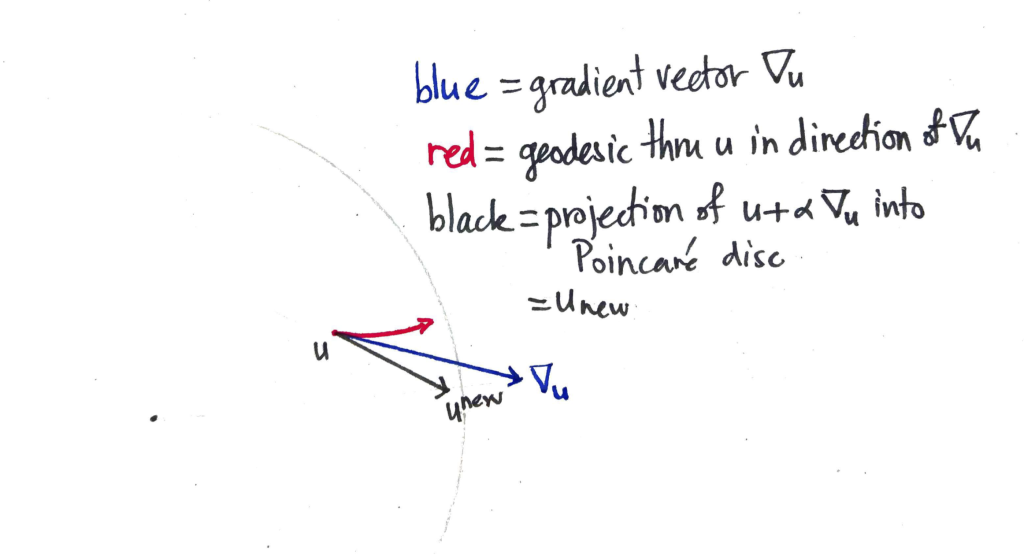

So far, so good. What the authors then do is simply add the (rescaled) gradient to obtain the new value of the parameter vector, which is fine, if you only take a small step, and so long as you don’t accidentally step over the boundary of the Poincaré disc! A friend described this as the Buzz Lightyear update (“to infinity, and beyond!”). While adding the gradient vector seems to work fine in practice, it does seem rather brutal. The root of the “problem” (if we agree to call it one) is that we aren’t following the geodesics of the manifold – to perform an update, we should really been applying the exponential map at that current point to the gradient vector. Geodesics on the Poincaré disc look like this:

that is, they are sections of circles that intersect the boundary of the Poincaré disc at right angles, or diameters (the latter being a limiting case of the former). With that in mind, here’s a picture showing how the Buzz Lightyear update on the Poincaré disc could be sub-optimal:

The blue vector $\nabla_u$ is the hyperbolic gradient vector that is added to $u$, taking us out of the Poincaré disc. The resulting vector is then pulled back (along the ray with the faintly-marked origin) until it is within the disc by some small margin, resulting in the new value of the parameter vector $u^\textrm{new}$. On the other hand, if you followed the geodesic from $u$ to which the gradient vector is tangent, you’d end up at the end of the red curve. Which is quite some distance away.